In 1983, a letter written by Enid Hardman to her cousin Rene Dempsey shed light on a significant chapter in our Dempsey family history. The letter recounted the story of their great-grandfather, James Dempsey, who, in the early 19th century, left his homeland of Ireland amidst turmoil and strife. He had a premonition, that “there would be no peace in Ireland for a hundred years.” History would later vindicate his foresight.

The 1830s-1840s saw Australia, a new colony, in dire need of labourers and farmers to cultivate its vast lands. The Bounty Scheme aimed to attract these individuals. James, yearning for a fresh start, decided to qualify for bounty assistance by listing his occupation as a ploughman on his Immigration Entitlement Certificate.

However, a further revelation in Enid’s letter suggests that James was more than just a farmer; he was, surprisingly, an accountant. He certainly possessed good reading and writing skills and this revelation would account for why he was able to acquire land in the new colony so swiftly after arrival – an achievement seemingly unattainable on a ploughman’s wages.

Despite the uncertainties surrounding their departure, James Dempsey and his wife, Jane (nee McLoughlin), embarked on a daunting journey with their seven children – John, Catherine, Mary, Jane, James, Ann, and Roseann. Their voyage began in October 1838 when they boarded the emigrant ship, Susan.

Before their departure, the Dempsey family spent time at the emigration depot in Londonderry, preparing for the challenges that lay ahead. These depots, essentially large sheds, offered a glimpse of the cramped shipboard conditions awaiting them.

On October 10, 1838, most passengers boarded the Susan, and the routine of ship life commenced. Four days into the journey, they encountered rough weather, a precursor to the hardships that would define their voyage. The water closets between decks also became clogged, posing an early inconvenience.

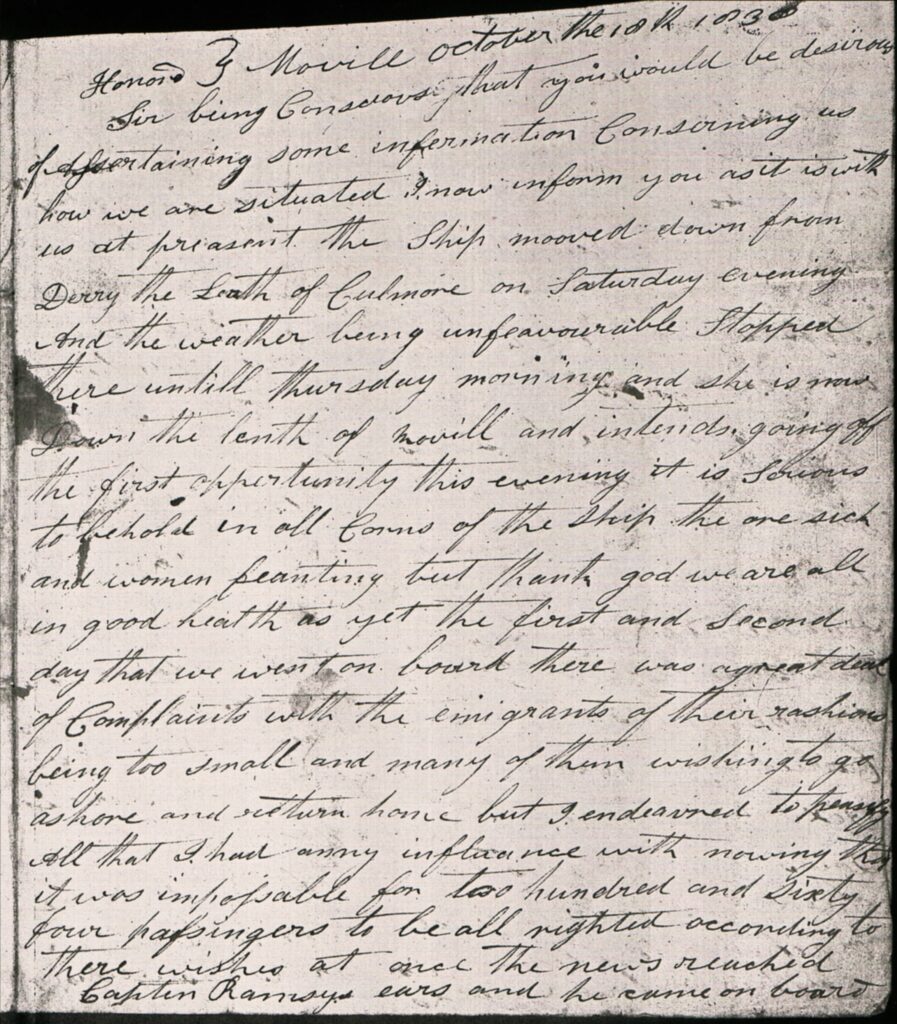

After several days anchored in Culmore Bay, the Susan moved to Moville, hampered by more adverse weather conditions. Seasickness plagued the passengers, and conditions became increasingly challenging. It was in Moville that James took the opportunity to send a letter back home, reassuring his loved ones.

James’s letter offers a window into the shipboard organisation and the emigrants’ well-being. Passengers were grouped into messes, each led by a designated individual responsible for fair distribution of rations. Discipline was enforced, and those who breached the rules would face consequences upon arrival in Sydney.

As the voyage continued, the challenges persisted.

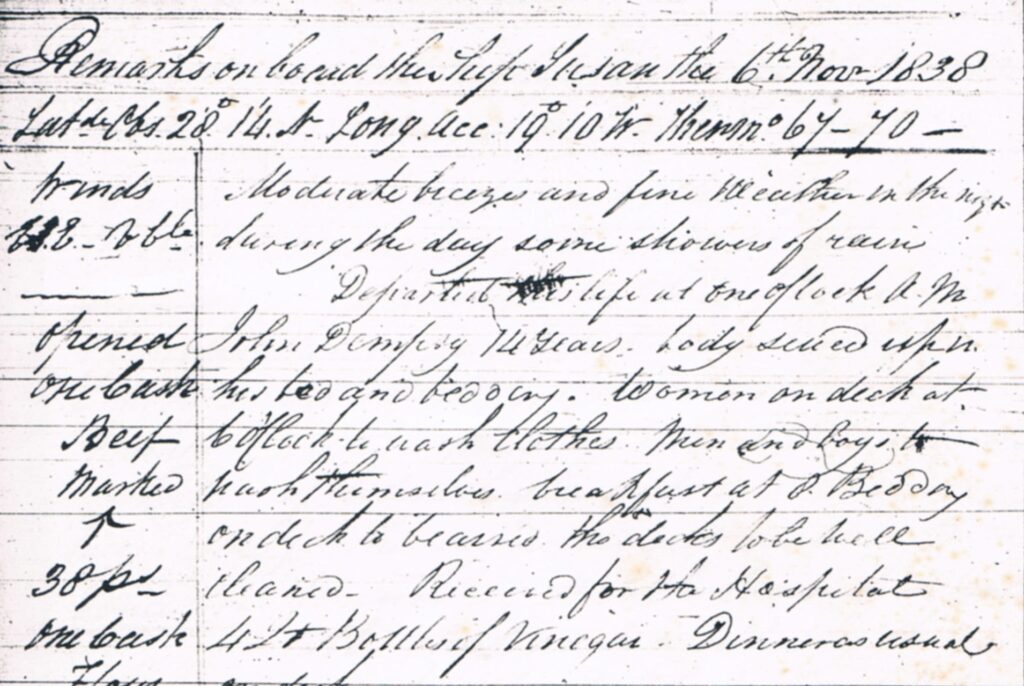

Young John Dempsey, only 10 years old, fell seriously ill from seasickness. His condition worsened in the days that followed. The ship’s surgeon recorded the grim details of his suffering.

Tragically, John Dempsey’s health deteriorated to the point of no return, and he succumbed to his illness on November 6, 1838, being buried at sea off the coast of the Canary Islands.

Despite the trials they faced, life aboard the Susan maintained a regimented order, thanks to the rules set by the ship’s surgeon, Charles Kennedy. Passengers found ways to pass their time, sewing, dancing, and singing, offering moments of respite from their struggles. Schooling was established for the children, and George Watson played the role of schoolmaster.

As the Susan sailed through the Tropics, the passengers had to contend with new challenges. Bowel complaints arose due to changes in climate and diet.

Christmas and New Year were marked with some small celebrations.

By the time Susan entered Sydney Harbour on February 1, 1839, the worst of their troubles seemed behind them. However, the presence of whooping cough led to further delays in disembarkation.

In his General Report of the voyage, Charles Kennedy praised the provisioning and care taken to ensure a healthy and orderly journey. With only four deaths (all children) and two births during the voyage, Kennedy’s assessment was largely positive. The passengers, aside from a few experiencing “nostalgic affection”, had remarkably improved their well-being.

The Dempsey family, like many others, had undertaken a challenging voyage to Australia, filled with hardship, loss, and resilience. Their story stands as a testament to the determination and hope that fuelled the dreams of those seeking a new life in a distant land.