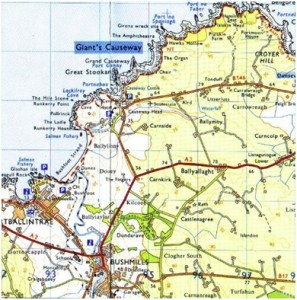

Family lore states that James DEMPSEY was born c1795 near the Giant’s Causeway in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. Bushmills was originally believed to have been his birthplace although emigration papers for James Dempsey, upon arrival in Australia, record him as being a native of the parish of Derrykeighan.

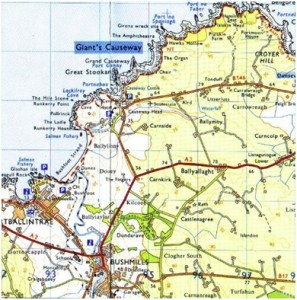

Research into James’s early life has been quite difficult but there is now enough evidence to confirm the location of the family home of James Dempsey and his wife, Jane (née McLOUGHLIN), in the parish of Derrykeighan. Nothing has been found, however, to suggest that James was actually born there. Material researched at the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland in 2013 revealed there was also a Dempsey family resident in the Tonduff district of North Antrim. So, could Tonduff, in fact, be the ancestral home of James Dempsey? While both Derrykeighan and Tondruff are in close proximity to Bushmills, the Tonduff district is the closer of the two and would back up the statement that James Dempsey was born “near” the Giant’s Causeway.

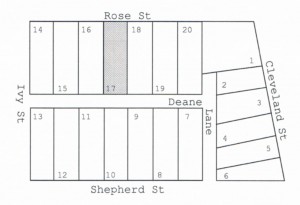

The location of Tonduff can be seen

in the 5th square across and 2 down

If James was born in the Tonduff area, and if he was not the eldest son, it would be highly likely then, that upon marrying Jane McLoughlin, he sought out his own residence at Derrykeighan, which would have been leased rather than owned, for them to grow their family.

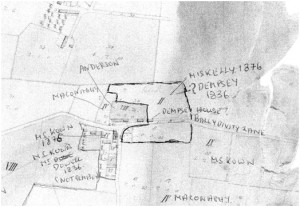

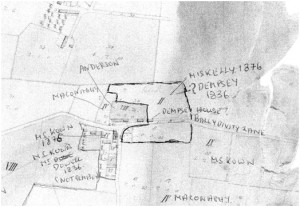

An 1836 survey map of the Ballydivity Estate, owned by the Stewart-Moores and located in the parish of Derrykeighan, mentions the name Dempsey as leasing one of the fields drawn on the map. Correspondence dated 1838 between James Dempsey and Captain [James] Stewart-Moore of Ballydivity corroborates a connection between the two men.

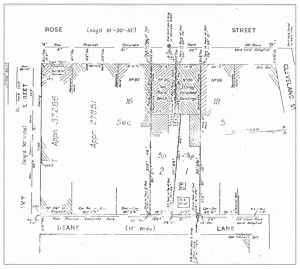

Drawing supplied by James Stewart-Moore in 2013 matching a survey map of 1836 showing the location of the Dempsey home immediately prior to James Dempsey and his family emigrating to Australia.

While there is no conclusive record having survived that confirms, beyond a shadow of a doubt, correspondence in 2013 between Jennie Fairs and the current owner of Ballydivity, another James Stewart-Moore, discussed and agreed on the likelihood that house ruins located in Ballydivity Lane were that of the Dempsey home marked on the 1836 survey.

Dempsey house ruins, 2013 – the fence line runs parallel to Ballydivity Lane

In a letter dated 1983 from Enid Hardman to her cousin Rene Dempsey, Enid writes that their great-grandfather, James Dempsey, left Ireland because “there was trouble with violence there, the same as is now. He [James] said there would be no peace in Ireland for hundreds of years.” How true his words turned out to be!

In the same letter, Enid also writes that James Dempsey was an accountant. In the 1830s-1840s, the new colony of Australia needed labourers and farmers to work the land (not accountants) and the Bounty Scheme was introduced to acquire these people. The desire to leave Ireland and start a new life with his family must have been strong, as James, to qualify for bounty assistance, deliberately recorded his occupation as ploughman on his Immigration Entitlement Certificate.

The discovery of Enid’s letter stating James’ occupation as an accountant helps to answer the questions of:

1. If James had been a ploughman, why was he able to read and write so well; and

2. How, after only being in the colony for a very short time, was he able to acquire land, something that could not have been done on a ploughman’s wages?

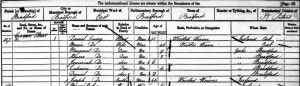

Whatever the reason for their departure, together with their seven children – John, Catherine, Mary, Jane, James, Ann and Roseann – James and his wife Jane boarded the emigrant ship Susan in October 1838 to start a new life in Australia. A copy of a Journal written by the ship’s surgeon, has survived giving us a rare insight into the life of a sea-faring emigrant.

On 10 October 1838, the majority of emigrants came onboard the Susan with their luggage. Once they had been allotted their sleeping quarters and sundry utensils, a pint of tea and biscuits were served to them and at 8pm they were ordered to bed. After four days of strong gales and squally showers with occasional hail, the Susan weighed anchor and headed down to Culmore Bay from Londonderry where for want of water over the flats it was necessary to anchor again. Following a further five days of remaining moored in Culmore Bay the Susan once again got underway only to anchor off Moville due to further strong gales with heavy squalls and rain. By this stage nearly all the passengers were confined to bed with seasickness, and although provisions for the day had been served out as usual, very few were in any condition to take anything.

Moville was the final Irish port where the emigrants could post last-minute letters home. Those who were able did so and among them was James Dempsey who wrote to Captain Stewart Moore Jnr of Ballydivity, “Dervock”, County Antrim.

Honord sir, being conscious that you would be desirous of assertaining some information conserning us, how we are situated, I now inform you as it is with us at present; the ship mooved down from Derry the south of Culmore on Saturday evening and the weather being unfavourable stopped there untill Thursday morning and she is now down the lenth of Movill and intends going off the oppertunity this evening; it is serious to behold in all corn[er]s of the ship the[y] are sick and women feanting but thank God we are all in good health as yet; The first and second day that we went on board there was a great deal of complaints with the emigrants of their rashions being too small and many of them wishing to go ashore and return home but I endeavred to peasify all that I had anny influance with nowing that it was impossible for two hundred and sixty four passingers to be all righted according to there wishes at once; the news reached Captain Ramsys ears and he came on board at Culmore and called all the passingers on deck and gave free liberty to all that pleased to go ashore and there was one man from Newtoun that went home and this is the reason that I write leaft the word would be carried home that we are ill treated and if it does, believe it not. For the hole passingers is put into seventeen messes and there is apointed one man head over each mess and I am appointed over one and it is there business to see the meat eaqually served out according to the number of the mess. We get our breaxfast about eight o’clock of good tea and one day pork with pea soop for our dinner and the next day beef with flour pudding mexed with suat; there is alsow rum, wine, figs and reasons for those that is sick and everything appears to be carried on in a verry judicious manner: there is six men apointed with the doctor for forseing (?) laws and if any is found pilfering from the other or giving insolence the one to the other or refusing to clean their births or sweeping upper or lower decks, the[y] are reported to the doctor and their names enterd in the registers book and when the[y] arive at Sidney, the[y] will be given up to the government and punished in proportion as their crime deservs, therefore I expect good order will be carried on. Now sir be pleased to give my kind love to my master, mistress Miss Ann and Miss Mary and little (?) Stewart and to all the men and let them know that there is no day that the[y] are out of my thoughts and let William Polock know that 1 wish that he would take word to my people to Bushmills and tell them we are all well. I now sir remain your kind and affectionate servant till death.

[Signed] James Dempsey

P.S. Let William Polock know that I forgot my reazor in the house and I wish him to go to John Mckelly as I think he must have it as he was the last I left in the house and keep it for my sake. Sir excuse the bad writing and blotting as the ship was heaving very hard the time I wrote it.

By 27 October, James and Jane Dempsey’s son John was suffering severely from [supposed] seasickness. The surgeon recorded in his journal: “John Dempsey, boy 10 years of age, suffering very much.” Several entries followed describing John’s decline until a final entry reports the sad reality for some emigrants who endured the long voyage to Australia – 6 November 1838, “Departed this life at one o’clock a.m. John Dempsey, 14 years – body served upon his bed and bedding … at 4 o’clock committed to the deep the remains of the deceased. Funeral service read by the Master.” John Dempsey was buried at sea off the coast of the Canary Islands at latitude 28.14N and longitude 19.10W. The temperature that day varied between 67 and 70 degrees Fahrenheit.

By 17 January 1839, whooping cough was also spreading at a mild rate and unfortunately for the Dempsey family, the eldest daughter Mary contracted the disease. Mary’s recovery was to remain slow and, by the time the Susan arrived at Sydney Harbour on 1 February 1839, Mary remained in a convalescent state.

After disembarking, James Dempsey was engaged by the Rev. Henry Carmichael from Williams River, NSW, for a yearly wage of £30 with rations. An emigrant brought out on the Bounty Scheme had to work for a minimum of one year for the person who paid the Bounty. Carmichael had been a schoolmaster and educational theorist who had been employed by the Rev. John Dunmore Lang as a teacher for the Australian College which opened in Sydney sometime after October 1831. In 1833, Carmichael founded the Sydney Mechanics’ School of Arts, the first of its kind in the colony. Then upon his appointment as the assistant surveyor for the Hunter district he left Sydney and established the Porphyry vineyard at Seaham on the Williams River. The vineyard, which survived into the early part of the 20th century, stopped production in 1915 and Lindeman’s bought the Porphyry name and trademark.

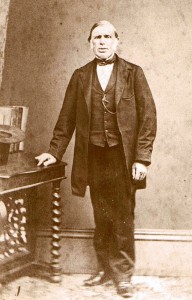

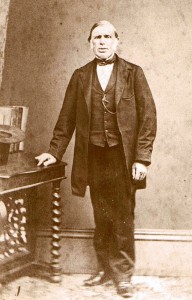

James Dempsey

Jane Dempsey nee McLoughlin

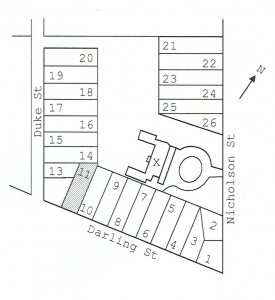

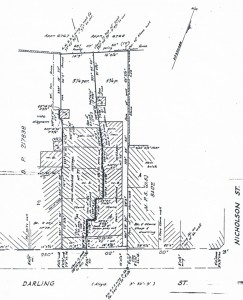

By 1841 James had obviously fulfilled his commitment to Carmichael as he and Jane were living back in Sydney. Shortly after he purchased land at Balmain being Lot 11 of Nicholson’s subdivision (75-77 Darling St, Balmain), and in 1844 James Dempsey had his son James Jnr build a weatherboard cottage and butcher’s shop on the land. Of strong Christian faith, James also helped establish the Wesleyan Church at Balmain in 1845. In 1857, James purchased land in Rose Street, Darlington which was to became his residence until 1870 when his wife, Jane, aged 75, died on 16 July 1870 following a three-week bout of bronchitis.

It is from the record of Jane’s death that I live in hope that there may still be family back in Northern Ireland. James was the informant for registration of his wife’s death, and it is safe to assume that he would have known how many children they had had. I already knew that the family had left NI with seven children – 2 males and 5 females – and that 1 male and 2 females had predeceased their mother, leaving 1 male and 3 females living at the time of Jane’s death. BUT James recorded on the death certificate that there were in fact 2 males and 2 females that had predeceased their mother AND 2 males and 3 females still living! Who was this extra male still living at the time of Jane’s death that I didn’t know about. The family and their descendants in Australia remained close so surely we would have known about this extra son had he also emigrated. Because no-one knew about the extra son, I believe that he must have remained in NI – possibly already married and settled when James made the decision to emigrate.

When James died on 23 September 1888, also of bronchitis, he was interred with his wife in the Wesleyan section of Rookwood Cemetery.

Grave of James & Jane Dempsey, Rookwood Cemetery, 2013

Throughout his life, James Dempsey remained an active member of the Wesleyan Church. His obituary printed in The Weekly Advocate reported that:

In the recent death of Mr James Dempsey the Newtown circuit has lost its oldest and one of its most respected members … [at Balmain] he was the first to open his house in which to hold services. When the time came for building a church, he not only gave to the utmost extent of his ability, but he spent much time and energy in collecting the necessary funds. The most prominent name connected with the rise of our cause In Balmain is that of Mr Dempsey.

Also included was a colourful description of Dempsey’s conversion to the Wesleyan faith:

In early life he was brought up in connection with the Church of England, and until some time after he arrived at manhood he retained that connection. But, though a strict adherent of the Church, he was not a converted man. His conversion took place in a remarkable manner. His own account, borne out also by his relatives, was to the following effect:

Returning home from the services of the church he usually attended, he passed a house occupied by a Mr Hill, which had been opened for services by the Wesleyan Methodists. It so happened that as he passed, one of the Irish local preachers residing in that neighbourhood was conducting the service. Mr Dempsey listened for a short time to the sermon, and then in a derisive manner called the preacher a “Ranter”, and passed on to his home.

In the early hours of the following morning a strange and startling noise was heard in the room where he slept. Whatever might have been the cause of the noise, it was interpreted as a call from God to his soul, which only a few hours previously vented its wickedness in opposing and deriding a servant of the Lord. His conscience so stung him that he could not rest. Under a deep sense of sin and danger both he and his partner rose to pray. Through the rest of the night they continued pleading with God for mercy. And as the morning light broke on the room it pleased God to set them both at liberty … He at once connected himself with the Wesleyan Church. He became a prayer-leader, and also a leader of a society class, and remained in these useful offices until he left Ireland for this colony.

The obituary then closed with the following words written by the Rev. W.B. Boyce:

I have known the late Mr Dempsey since 1847. His character for Integrity and industry stood high, and his Protestantism was a striking characteristic of the feeling of an Irishman … I do feel the highest respect for his genuine character, and the impression of which was common to all who knew him intimately.

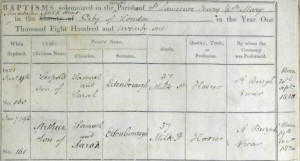

I have been very fortunate that there have been descendants of James and Jane Dempsey in Australia that have kept all manner of family documents and memorabilia. But it is James’s ancestry back in Northern Ireland that is my brick wall. Unfortunately, the parish register for Derrykeighan is among the records destroyed in the 1922 fire at Dublin’s Four Courts. On my 2013 visit to NI I spent 5 days researching at PRONI and came away with what may be a possible lead – a Daniel Dempsey was a churchwarden and sidesman of the parish church of Billy, Co. Antrim and the Billy parish encompasses the town of Bushmills as well as the townland of Tonduff and the Stewart-Moore home of Ballydivity.

child and enjoying the fabulous elephant rides that are such taboo these days. I only wish I had been photographed with the elephants at the time.

child and enjoying the fabulous elephant rides that are such taboo these days. I only wish I had been photographed with the elephants at the time.

![Sydney Infirmary, 1870 / [attributed to Charles Pickering] the image is from the collections of the State Library of NSW SPF / 176](https://edenborough.info/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Sydney-Infirmary-1870-SLNSW-SPF-_-176-300x255.jpg)

As a child growing up in the 1960s, the cold seafood buffets and barbecued lunches we enjoy today in Australia weren’t even a figment of our imagination back then. Instead, we sat through a variation of the typical English Christmas dinner of a roast and baked vegetables. I say a variation because my stepfather was Italian and this meant that we sat through a MASSIVE Christmas lunch. If it was only our immediate family for lunch it would start with either, soup, or pasta, followed by roast lamb AND chicken with the usual baked vegetables, including at least two types of beans, as well as peas or zucchini. Dessert, if we wanted it, was usually Neapolitan ice-cream.

As a child growing up in the 1960s, the cold seafood buffets and barbecued lunches we enjoy today in Australia weren’t even a figment of our imagination back then. Instead, we sat through a variation of the typical English Christmas dinner of a roast and baked vegetables. I say a variation because my stepfather was Italian and this meant that we sat through a MASSIVE Christmas lunch. If it was only our immediate family for lunch it would start with either, soup, or pasta, followed by roast lamb AND chicken with the usual baked vegetables, including at least two types of beans, as well as peas or zucchini. Dessert, if we wanted it, was usually Neapolitan ice-cream.